In the 1970s one of the greatest threats in air travel was the fear of being hi-jacked. For Annette Lynton Mason from Corsham this fear became a reality, when her family were on board a plane seized by terrorists. She shares her story with Mary-Vere Parr.

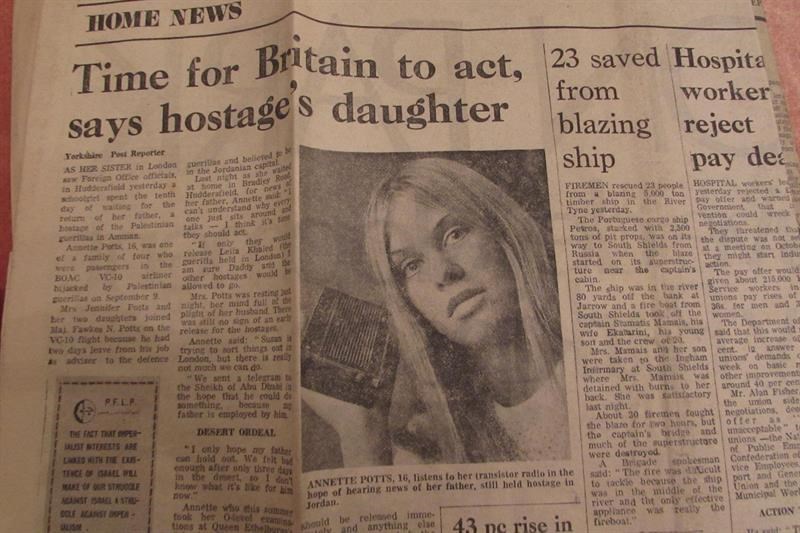

A Iarge, plastic box overflowing with newspaper cuttings sits on a pink velvet chaise longue in the drawing room of Middlewick House, near Corsham. Picking the fragile, yellowed pages out one by one, the remarkable story of a plane hijacking in a hot Middle Eastern desert unfolds. Back in September 1970, it was a tale that grabbed the world’s headlines and threatened war. Today, in wintery Wiltshire, it’s a story that actress Annette Lynton Mason, who was the schoolgirl Annette Potts pictured in many of the newspaper reports, is reliving.

Airborne adventures were nothing new to Annette. As the daughter of an army officer posted abroad, she was sent to an English boarding school, Queen Ethelburga’s in Harrogate, and often flew alone to join her family for school holidays.

The journey on 9 September 1970 on flight BA775 from Bahrain to Beirut and London should have been routine. Annette (Nettie), 16, and her sister Susan (Susie), 21, were returning home with their mother, Jenny. Their father, Major Fawkes Potts, who worked for the Abu Dhabi Defence Force, was spending a few days leave with them.

But, after lunch on the plane, Annette recalls how she saw the curtain dividing first from economy class lifted and people walking through “looking sheepish and alarmed”. “I remember a man on the intercom saying ‘Please be sitting down and tie yourselves up’, which made my sister and I giggle,” she adds.

Behind the first-class passengers, a “youngish” man appeared. “He must have had a gun, but I don’t remember that - just his face and his wild eyes. My father told me he thought he was on drugs.”

In the flight deck, the first hijacker was already holding a gun to the pilot’s head. A third hijacker jumped up in the row behind Annette and Susan. It was mentioned that there was a fourth, undisclosed hijacker. Annette thought that might have been the foreign woman sitting next to her: “She kept telling me again and again why she was going to London, and who was meeting her there, it seemed rehearsed. She disappeared immediately after we landed in the desert.”

The VC-10 landed and refuelled at Beirut where three more guerrillas came aboard and handed out landing cards with the destination “Revolution Airport”. It was the fourth plane in as many days to be hijacked by the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP). One hijack had been foiled, but the other three planes ended up at Dawson’s Field, a remote desert airstrip near Zarqa in Jordan, dubbed by the PFLP “Revolution Airport”.

After landing in a sand storm, the VC-10 sat on the desert airstrip for three days. The hostages - 10 crew and 105 passengers, of whom 57 were British and 30 were children - were all pawns to bring pressure on Britain to release Leila Khaled, theunsuccessful hijacker of an Amsterdam to New York flight that landed at Heathrow, who was being held in custody at Ealing Police Station in London.

Annette describes the desert wait as “rather like a dream”. “Although we were right in the thick of a world crisis I felt more like an outsider looking in on a bizarre dream,” she says. One child had some stick insects in a box. Annette remembers being delighted to see them: “It made the situation normal for a few minutes.”

“No passengers had died in any hijacks at that point so the fear was different then,” she continues. “The worst thing was seeing my mother suffer. Her fear for us still upsets me today, more now than it did then as I understand it better.”

But when some hostages were released and one offered to secretly smuggle out letters, the danger really struck home. “Writing a letter to my boyfriend, I realised that it might be goodbye,” Annette recalls.

They whiled away the time “talking and meeting people”. The hijackers were friendly: “They let us listen to the radio and offered us cigarettes – I still have the cigarette packet that one gave me.”

But conditions were perilous. It was cold at night, hot by day. “I slept on the floor between the seats, luckily we had a bit of space after the lady next to me had gone,” Annette says. Food sent out by the Red Cross was running low, and there were two three-month-old babies on board as well as several pregnant women.

Then, on 11 September, there was what Major Potts called “a ghastly alert”. Everyone was told to stay in their seats as the guerrillas took off all the hand luggage. Susie’s epilepsy medicine was stranded in one of the bags on the airstrip. A senior steward persuaded the guerrillas to let her retrieve her pills and all the passengers were able to stretch their legs and enjoy walking around briefly, but the day’s saga was far from over.

The hijackers asked the hostages to write telegrams to send to their governments, adding: “We don’t want to kill you but, if we have to, I am afraid we shall.” To underlie the threat, they brought dynamite aboard.

“We were sitting there desperately silent and pretty tense, writing these stupid telegrams,” Major Potts recalled. His read “Our situation is extremely grave and we do ask you to immediately to [sic] request the government to release Leila otherwise we can see no hope.”

Then a woman hijacker started going up and down the plane shouting “Your Government don’t like you, they don’t like you. You’re all going to die.” Annette remembers a teenage boy strutting the aisle behind her wielding a large gun.

On 12 September, the Potts entered their third day of detention on the plane. Suddenly, the hijackers issued a five-minute warning that the women and children would be taken back to Amman and released. “I barely had a chance to kiss my wife and elder daughter,” said Major Potts. “And I didn’t have a chance to say goodbye to Annette.” These words obviously haunt Annette. “It makes me sound like I didn’t care,” she says. “I was an army brat, for once I did as I was told, ordered by my father to get off the plane. There was no emotional scene because we thought he would be following shortly. We just waved to him through the window.”

In fact, her father and the other men were lined up outside, and told to open their mouths to avoid biting their tongues as they watched the hijackers blow up the planes. Then they were herded into minibuses. Major Potts, the crew and a couple of the other men were selected to go in the last bus which veered away from the rest, heading to Wahdat, a refugee camp on the outskirts of Amman. The men inside were told that they were prisoners of war. Major Potts’ ordeal was far from over.

But neither was Annette’s. First came the shock of arriving at the Intercontinental Hotel in Amman to face the world’s press. “After days sitting on a plane in the desert we assumed nobody knew we were there,” she says. “Even if you hear you are a news story, the scale doesn’t register.”

Early the next morning, Jenny and her daughters were reluctantly hurried to the airport and flown to London. Back home in Huddersfield, they waited for news of Major Potts. In an interview for the Huddersfield Weekly Examiner, Annette tells of the family’s frustration and efforts to secure her father’s release, including sending a telegram to Sheikh Zayed of Abu Dhabi, his employer. “One thing that did help was the fact that Daddy is an Army man,” she told the Yorkshire Post. “He was marvellous on the aircraft while we were being held. We all knew he would cope with whatever happened and believed that we would see him again.”

Finally, on 25 September, Major Potts was rescued by the Jordanian army. The last of the hostages were released on 29 September and Leila Khaled on 30 September.

Major Potts described his hijackers as “nice fellows”. “I’ve got a lot of sympathy for them,” he said. It’s a sympathy his daughter shares: “I was upset when father told me that some of the hijackers had been shot during the Jordanian army rescue. I didn’t hate them then, I don’t hate them now. I think they have a cause but it’s misguided at times. I was not a particularly political 16-year-old but that was the conclusion I came to then which I still believe.”

After posing for the family reunion photographs, Annette returned to Queen Ethelburga’s school, where, she says, her ordeal was ignored. “A lovely girl from the plane that I stayed in touch with was at another school. I was a bit jealous as she was given flowers and a big welcome,” Annette recalls. “But my school didn’t mention it, they were just irritated I was returning LATE!”

First published in Wiltshire March 2021 now updated and amended with Annette Lynton Mason's corrections.